The 2021 SXSW Film Festival, although forced virtual due to the Covid-19 pandemic, brought many interesting documentaries, introducing topics that remain out of sight for a lot of viewers. The opiate epidemic was covered thoroughly and in the feature documentary “The Oxy Kingpins” (the kingpins are not who you think), as well as some other topics brought from others. “The Box” showcased the effects of solitary confinement on prisoners, “Under the Volcano” showcased the rich history of the music industry, and “Lily Topples the World” made exciting the world of dominoes and YouTubing.

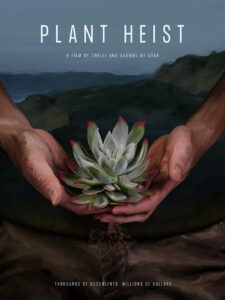

One of the most interesting documentaries I saw during the festival, which also happened to be a documentary short, was the intriguing film “Plant Heist.” The film is directed (and pretty much everything else) by the de Cuba siblings, Chelsi and Gabriel. The documentary highlighted the harm of botanical poaching, a concept I have never considered but now understand the ramifications of. The subject of the documentary was a succulent plant called Dudelya farinosa, which fetches extremely high prices in China, and has the effect of causing harm to the coastline of Northern California.

During the festival, I had the chance to talk to the de Cubas about their movie, their inspirations, struggles and surprises during filming, attending their first SXSW festival, and more. The interview follows below. And don’t forget to check out our review of “Plant Heist.” You can read the review here.

Hi, and nice to meet you. Can you tell us a bit about yourselves? What got you interested in filmmaking? Is this your first film?

Chelsi: For me, I got interested [in filmmaking] through my brother, who went to film school. I was on a different path in Public Relations/Marketing. He was always talking about film, and I always had this interest so I was dabbling in it with him. We would do some fashion films and commercials together, and we seem to work well together and so then I got more and more involved. Then I moved out to California from New York and started working in a production company out there. Then, yeah, we hopped on this project, and it’s our first film.

I watched the film this morning, and, I’m trying to remember this right, Gabriel…you did the cinematography?

Gabriel: Yeah. We co-directed, I shot the film and I did the editing as well, although Chelsi worked very much as an Assistant Editor. I manipulated Premiere Pro, is what I’m trying to say, and we both made the decisions on the story arc in that regard. And as Chelsi said, I went to film school in Florida, I moved out to California four years ago working as an assistant cameraperson mostly in commercial and sometimes documentary. And I kind of always wanted to tackle a story…I just didn’t have any good story to tackle. I was kind of just ‘waiting’ for that, for something in a documentary capacity because I was always attracted to documentaries, and so has Chelsi.

We were very interested in that and this just kind of hit all at once. It all started from a news article that a friend of mine sent and it was one of things where you just read and you’re like ‘wow, this is too good not to make a visual story out of.’ This reads like a spy novel or something—and it’s about plants…and this is bizarre, and we need to tackle this as soon as possible. And it’s happening in our backyard—this is happening in Mendocino [CA], so it wasn’t too far from where we’re at.

Chelsi: Yeah it was pretty local, which made it easier on our end…budget wise.

I was amazed at the prices that these plants, the succulents can garner in Asia. For those who may not know what the Dudleya farinosa is, can you describe it?

Gabriel: Yeah, so the Dudleya farinosa is a plant that is not exotic to California and it’s not scarce. It grows all along the cliffs, all the way down to San Diego, all the up to Mendocino, and it’s a beautiful plant. I first saw it when I was on vacation; it’s a succulent that grows on the cliffs and it’s huge and beautiful.

Dudleya farinosa is a plant that is not exotic to California and it’s not scarce. It grows all along the cliffs, all the way down to San Diego, all the up to Mendocino. It’s a beautiful plant.”co-director gabriel de cuba

But what started happening over the years were these poachings. And that’s when people started to take notice. [Dudleya] is a very unique plant; it grows off the cliffs, and it’s hard to grow because of the conditions it needs. We learned a lot about what we know about the plant from the person you saw in the film, Stephen McCabe. He’s the professor at UC Santa Cruz…he’s the world expert on it, and he’s a wealth of knowledge. You only see him shortly in the film, but we talked to him for hours.

Chelsi: Yeah, it started with a different Dudleya species [Gabriel: Dudelya Pachyphytum] and it started in Cedros Island in Mexico, where they would go and poach them from there. But it was really treacherous—they’d have to take a plane, and a boat, and then hike up with all these dangerous types of conditions. So then they found Dudleya farinosa, which was just on the cliffside in California, it was much easier. But still, poachers are taking some risks, sometimes putting climbing equipment on and getting on the side of the cliffs to take these plants.

The documentary talks about supply and demand for the succulents in China, their growing middle class, etc. Did you find any other reasons for the huge demand for these ornamental plants?

Gabriel: Yeah, that was certainly a driving force behind it. We never went obviously to South Korea or China, but the best we could do is talk to journalists, talk to law enforcement and their view of what was going on and talk to experts about the plant. But there’s so much more here to explore than a 17-minute documentary.

This is definitely a topic I didn’t know anything about, and hopefully this documentary can bring awareness. Did you learn anything during filming about the harm to the terrain/ecosystem from poaching Dudelyas?

Chelsi: Yeah, I think one of the things that he touches on [Stephen McCabe] is the erosion and not knowing yet the effects that could happen from taking these plants. There’s a cycle that goes on—it affects the bees, the hummingbirds…all of this goes on and on. But since it’s a recent thing, they don’t have enough to know what’s going to happen long-term. They can surmise from other things that have been taken from the wild.

Gabriel: Yeah, he could do his best to assume what was ‘going’ to be impacted, but because it’s so new they don’t have hard data on exactly what is going to happen until more time passes with those plants removed from the wild. But like Chelsi said, it’s a snowball effect.

I wanted to talk about the article or inspiration that clued you guys into this issue. Can you elaborate?

Gabriel: I first knew about this because I saw them—I’m a plant lover as well—and I was on vacation and I saw these plants on the cliffs. It was a surprise to me to see succulents covering the cliffs of California and I took a bunch of photos of them. A year went by and my friend Georgia Peppe, who is Associate Producer for the film, sent me an article in the New Yorker explaining the poaching that was taking place in the same county that I took that vacation in one year ago with the same plants I photographed. I immediately thought ‘this needs to be told, and it needs to be told visually, but how do we do that?’

Can you explain why you picked a short for your telling of this story? Was it just the right length for the material?

Gabriel: I was thinking what the right length is to tell the story. And I’ve seen some great micro-docs around the 5-minute mark, and I initially thought that…but then the story takes you places. You start calling people to get interviews and their answers elicit more questions. They’re like ‘hey, you should go talk to this person’ and then we’re talking to that person. And it starts to deserve more time.

Chelsi: I think the biggest thing was getting the interview with Patrick Freeling, the Game Warden you see for most of the film. He was just so enthusiastic about getting the story out and a champion for protecting these plants. And it took a while to actually get that interview, because we had to go to the higher ups of California Fishing and Wildlife to get that permission, which took a while. But after we got that interview, we were like ‘whoa.’ I mean he was so good, and such a character and such a protagonist.

That was one of the things that struck me. You think of Game Wardens, and then you see him talking about tracking poachers, putting on camouflage, etc.

Chelsi: Yeah, that’s so many people’s favorite…like every time I watch it with a friend they’re like ‘the Ghillie Suit!’ But yeah, he’s been fantastic through this whole thing with us and just trying to get everybody involved, the key players. And he really helped us to secure those other interviews.

Gabriel: That was key. Patrick [Freeling] was key to everything…because, every article that you read, Patrick’s in. He’s the guy who broke it. He’s in the ‘New Yorker,’ he’s in the ‘New York Times’ as an article. He followed his detective instincts, he thought ‘there’s something here, I just don’t know what it is yet.’ And boom, he broke a big case with hundreds, thousands of Dudleya inside of a van and that’s when everyone started to take him seriously as well. I think any type of law enforcement might be apprehensive of the press, but we saw this as a potentially great story for everyone. Game Wardens CARE about nature. And it really shows.

One thing that shocked me is that there is only around 400 Game Wardens for such a large state, and one often suffering from wild fires, etc.

[Both laugh] Yeah, that’s a whole other documentary.

I wanted to ask about filming. Were there any obstacles? Was it hard to complete this project?

Chelsi: Yeah, I think with any big creative pursuit [getting started] is always a big obstacle. But once we started, we had a good momentum going. We were lucky enough to get some upfront funding from a production company I work with and get equipment for free from a production company Gabriel works with. That was huge, and it kind of gave us that motivation.

I think where we really came up with challenges was in the edit room. That was right when Covid hit, and we had one interview left to get—with a State Senator who was working to pass a Bill to protect these Dudleya, which he did—which we never got. So we just decided to go into post-production because we couldn’t wait until the unforeseeable future until things open back up again. Getting through the edit was a lot of commitment. We’re siblings, and there’s advantages and disadvantages to that, of course. We can be very upfront with each other and get into little things, but there’s the advantages of we’re over it ‘like that ‘and move on. The biggest challenges were getting through the edit and putting the story together.

Beyond “Plant Heist,” documentary filmmaking is a great interest to both of us. And we have a bunch of different subjects we’d like to tackle, but right now they’re just ideas…we want to give “Plant Heist” the space it deserves to see where it goes.”co-director gabriel de cuba

Gabriel: I think once we got over the first hurdle of Freeling’s interview, the rest of production was great. There weren’t many hurdles. We would go to Monterey or Big Sur and grab our b-roll, then grab some more interviews. The hurdles after that were all in post-production, because the world was kind of crazy when Covid first hit. This was a passion project for us. No one was paying us to do this, and passion projects [then] often got put on hold because no one knew what was happening with the world on a global level. Some self doubt that creeps in. There was a bit of loss of momentum on post-production. You have a lot of footage, and you have to go and piece together the story. And it was our first documentary, too.

But we learned so much in post-production about story-telling and story arcs. We had to strike the balance between entertaining and educational. But one of the best ideas—which we’ll use in all documentaries in the future—is getting all the interviews transcribed, which was Chelsi’s idea.

Yeah, that has to be challenging, with edits, Covid etc. But I think you guys did a great job with this, and when I got to the end of it, I didn’t really want it to be over.

Gabriel: That’s definitely what we want!

Do you guys have any plans for the future, filmmaking-wise, or anything you hope audiences will take away from this film?

Chelsi: For the future, we’re open to anything as far as “Plant Heist” goes. Like Gabriel said, we really just touched the surface. This problem, plant poaching, is a global problem. And this is just one story of how it happened. And then we have other ideas for what might be next for us, and those might include documentaries.

Gabriel: Yeah, like she said, we really just scratched the surface. There are so many plants that are sought after and worth so much money.

Beyond “Plant Heist,” documentary filmmaking is a great interest to both of us. And we have a bunch of different subjects we’d like to tackle, but right now they’re just ideas. We want to give “Plant Heist” the space it deserves to see where it goes. And maybe in our next project, if it has backing, we can tell more. We really wanted to go to South Korea to tell the next part of the story. With budget constrictions, you can’t do everything you want or what the story might deserve. You just have to do your best.

A big thank you to Gabriel and Chelsi de Cuba for participating in this interview and Jim Dobson from PR for setting up the interview for us.